Architecture’s centuries-old pact with power left it economically irrelevant. Now, individual and information power offer a path to redemption.

Location, size, and number of rooms. In this order, these factors determine the value of properties in cities worldwide.

Architecture, who happen to be the entity (mainly) responsible for depicting properties (in some cases, also spaces) in cities, has surprisingly little (close to none) economic influence on property value outcomes.

To illustrate, in any given city, two well-preserved buildings with two-bedroom apartments of similar size, in the same neighborhood, will be valued at almost identical price points. If one of those buildings happened to be designed by an extraordinarily significant architect, the property value might increase by 1% to 2%. Maximum.

When it comes to architecture and real estate, the former has been rendered economically (practically) invisible. This is not an anomaly at all. This is the foundational rule of the global real estate market, and it reveals a profound, self-inflicted crisis at the heart of architecture.

Today, architecture is paid for only at the “birth” of the building, essentially as a service fee. For the rest of the building’s life, while it generates immense economic value through rent and resale (spanning decades or even centuries), architecture has been severed from the financial property value (that it has helped to create).

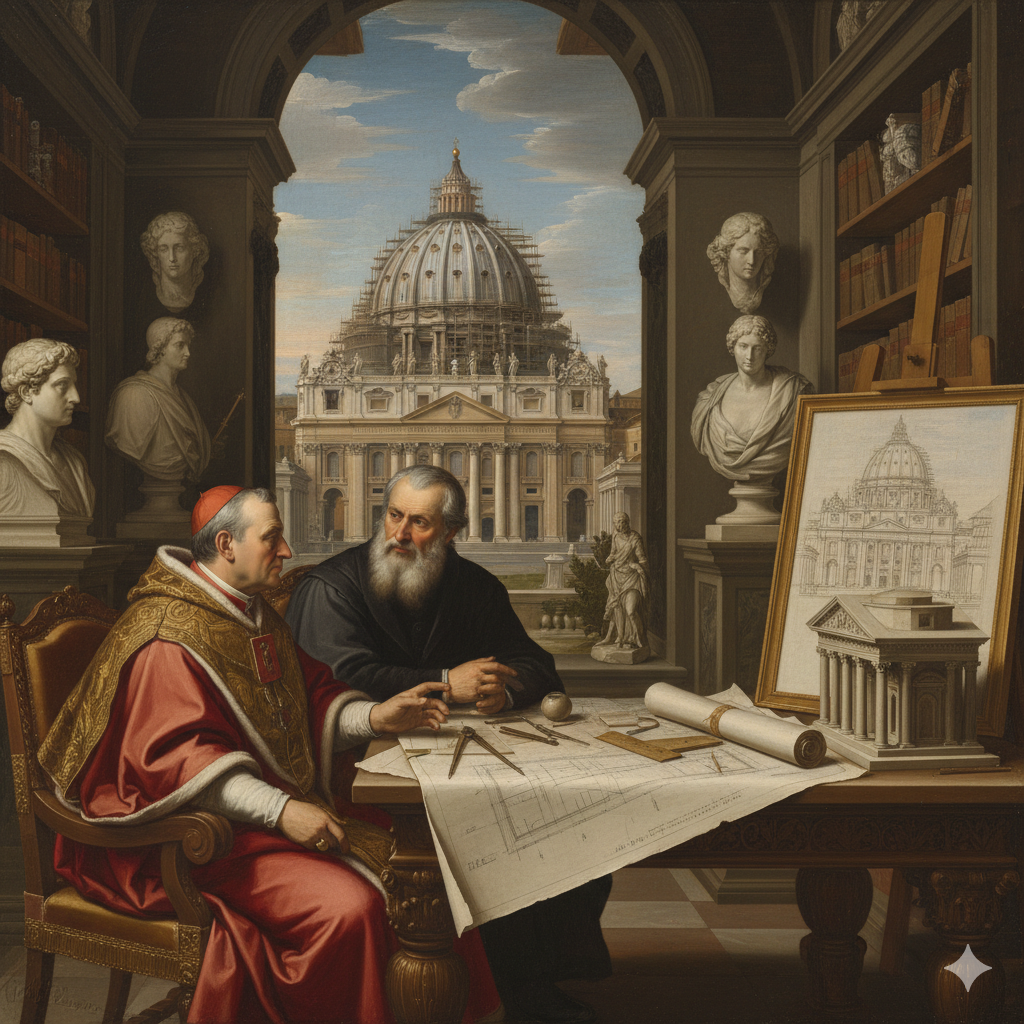

How did architecture get here? Well, the current connection between architecture, property value, and urban development is not a recent failure of taste. It is well explained by the relationship architecture established in its early years with empires, kingdoms, and religious organizations first, followed by the State and an industrial elite second.

With empires, kingdoms, and diverse religious organizations, architecture was always ready to attend to the desires of their authorities (their clients), always prioritizing their wishes at the expense of the common good.

To illustrate, not that long ago, architecture focused primarily on designing the exteriors of palaces, while cities expanded way beyond their scope. This fact contributes to architecture continuing to be seen as a city landscaper rather than a city planner.

The same principle applies to the role architecture played in the Industrial Revolution, with a huge focus on the appearance and design of industries, rather than understanding and contributing to the industrial infrastructure.

On the path to establishing this design-oriented perspective, architecture primarily focused on legitimizing power, creating a “correct” and “rightful” vision of spaces that has been highly effective in reinforcing this very social order.

This cage keeps architecture encapsulated in this outdated artistic realm, always grasping with the tip of its nails to its sacred birthright of being this source of “correctness and rightfulness regarding spaces,” together with its loyalty above all to the elites.

The fact that “not everyone understands architecture” or “not everyone enjoys architecture” is often attributed to the wrongness of the human experiencing it.

In other words, when a building is ugly, uncomfortable, or confusing, it is never the architecture’s failure to communicate, accommodate, or delight. It is as if architecture is not even made for humans.

Well, while architecture was looking (and still is) the other way, clinging to its old patrons, the world changed. By prioritizing this toxic loyalty to the elites, architecture rendered itself irrelevant to the most significant driver of value in the modern world: the market.

From this perspective, architecture became not just a cultural problem – it became an economic one. The real estate industry developed a standardized, easily quantifiable language (square meters, zip code, room count) because that is what the mass market understands and can trade on. With its subjective talk of “spatial quality” and “materiality,” architecture ended up having no place in the equation, location + size + number of rooms.

Yes, elites are still major game changers in societies and cities worldwide. Still, other kinds of societal powers have been emerging – information power (the ability for knowledge, data, and critique to be generated and distributed by anyone, anywhere) and individual power (the empowered consumer).

Architecture, somehow, seems to be utterly oblivious to them. It continues to pitch its services to corporate boards and state committees, the modern equivalents of its old patrons, while ignoring the vast, untapped power of the networked individual.

With individuals having more choice, more access to information, and more agency than ever before, they have become the new patrons, demanding spaces that serve their needs rather than an abstract architectural ideal.

Architecture needs to start acknowledging that, as of 2025, there are no humans inhabiting the earth’s surface who, out of their own choice and will, would prefer the ugly, the bad, and the uncomfortable.

It has never been a better time for architecture to experiment with information and individual power, reclaiming its well-deserved authority to dictate and heavily influence the market it is part of.

Architecture needs to finally position itself as a necessary instrument to shelter human relationships, making life more comfortable and better.

Instruments, theories, information, know-how. Architecture already has a lot of it. Architecture can change and be a part of the contemporary world.

Architecture only needs courage.